Group and Team Processes

See also: Group RolesOur page An Introduction to Groups and Teams explains that we define a group as people who agree that they share a common purpose, ideas, beliefs or experience. They must also frequently engage with each other, and work together on shared tasks. This definition therefore focuses on the tasks or purpose of the group.

However, in any group, there will also be underlying group processes happening.

Members of the group are likely to be very aware of the group tasks, and focused on their achievement. However, they may be less aware of the processes—and this may hinder the achievement of group objectives.

This page describes some models of group processes, to help you understand more about what is happening in any group.

What Are Group Processes?

The content of a group’s work is its tasks: effectively, the group’s ‘what’ and ‘why’.

Group processes are ‘how’ a group behaves.

They include how the individuals within the group interact with each other, how decisions are made, how problems are solved, and how the group communicates internally and with other people.

Many people are generally unaware of group processes. They are probably aware that they are happening, but not how (see box).

Content vs. process: an analogy

In a paper on group membership in 1998, Kwiatkowski and Hogan suggested that chewing gum provided an analogy of content vs process.

The gum itself is the content.

The chewing is the process.

Someone chewing gum is aware that they are chewing. However, unless they thought about it carefully, they would probably be unable to say whether they always chewed on one side or the other, or where their tongue was during the process.

Similarly, group members are usually aware that there is a process, but not precisely how it works—and certainly not precisely enough to be able to influence or change it.

Models of Group Processes

1. The Johari Window

The Johari Window was developed by Joseph Luft and Harry Ingham, hence its name. It provides a way of thinking about how individuals operate within groups.

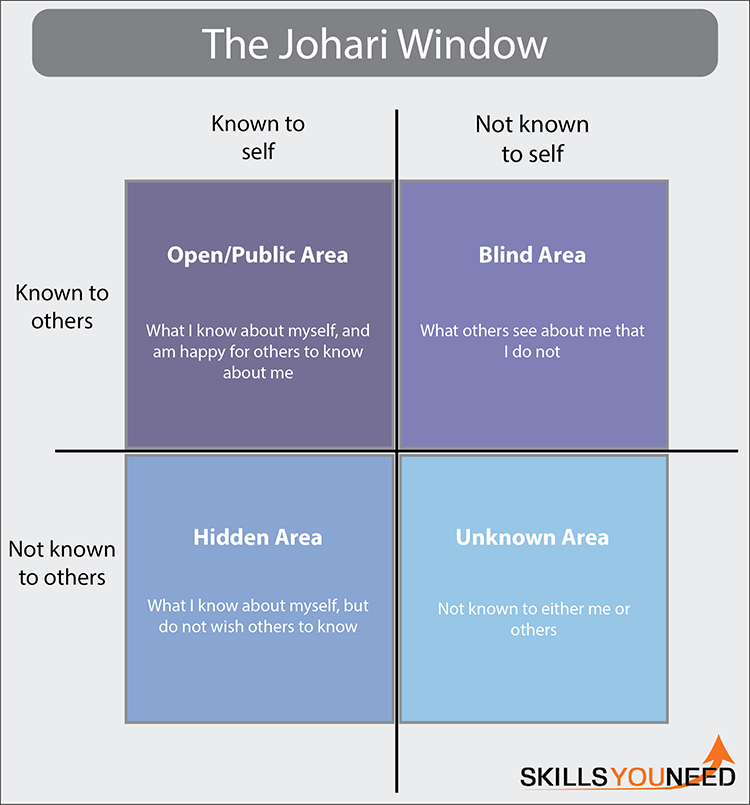

The Johari Window separates information about an individual by whether it is known to the individual and to others in the group.

This creates four quadrants (see diagram).

There are several aspects about this model that are interesting. For example:

The information included in each quadrant can change for anyone when they are in different groups. For example, there may be information that you are prepared to share with your friends that you would not want your work colleagues to know about.

The size of the Hidden vs Open/Public Area can be particularly informative. Some people prefer to keep a lot more information private. Introverts, for example, have a general preference towards not sharing so much information. However, when more is hidden, you have to be aware that people have less information on which to draw to make judgements about why you are behaving in certain ways. This may be mean that they make more assumptions about you—and that these may not be accurate.

-

Keeping information private (Hidden Area) is perfectly appropriate. There are many times when it is entirely appropriate to keep information private. For example, your colleagues do not need to know all the details about your family party at the weekend (or worse). Professionally, there may also be plenty of information that you should not share with others (and for more about this, see our page on Confidentiality in the Workplace).

Working together as a group is much harder if the Blind and Unknown Areas are larger. It is generally easier to work together when you know more about each other (a smaller Unknown area), and about yourself (both the Blind and Unknown areas). Self-understanding is particularly helpful when working in teams (a smaller Blind area), because you then have a better understanding of how you might be perceived by others.

2. Schein’s Observational Framework

Edgar Schein was one of the gurus of process consulting (the practice of facilitating processes). He described a framework for assessing information.

He noted that some information is truly objective, but other information comes from our own reaction to other people, and is therefore subjective. This is not to say that subjective information is bad, but it may be less accurate.

In considering any interaction with other people, or within a group, it is important to distinguish between those two.

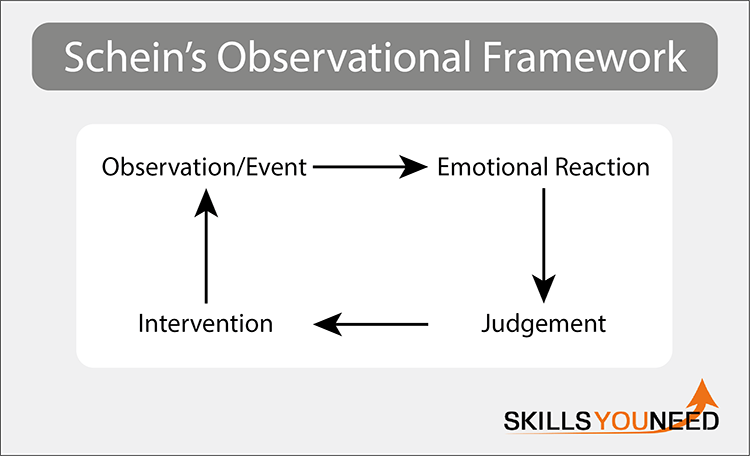

Schein’s model described how information was processed (see diagram).

Schein suggested that we observe an event (e.g. someone speaking to us), and have some kind of emotional reaction to that event. We then analyse, process and judge the event based on both our observations and our feelings. Finally, we make some kind of intervention (e.g., replying to the original speaker).

It is important to understand that both our emotional reaction to the event, and our judgement, can be influenced by many factors, including previous experience, stereotypes, expectations and how we are feeling that day or about the other person. There are, therefore, several very subjective steps between objective data (the observation or event) and our response.

This means that it is entirely possible that the intervention we make can be both entirely justifiable (to us), and completely incorrect.

Schein described several ‘traps’ that people could fall into at different stages of the cycle. These were:

The event might be misperceived: that is, our observation of what happened or why was incorrect, or coloured by expectations or prejudgements.

Our emotional response was inappropriate, again perhaps because of expectations or prejudgements that affected what we saw or heard.

We might therefore make a rational judgement, but based on incorrect data (the misperception and/or inappropriate emotional response).

The intervention itself is therefore also based on incorrect data (the misperception, inappropriate emotional response and/or incorrect judgement).

Improving Group Processes by Using These Models

These models are of course interesting in themselves. However, they are chiefly useful if you use them to improve the processes within your groups. You can do this by, for example:

Considering what information it would be helpful to surface—both from you and from others—to reduce the size of the hidden and blind areas of the Johari Window. Nobody is saying that you need to disclose every last detail of your life, but sometimes giving a bit more away is helpful!

Asking questions to reduce misperceptions and misunderstandings, or to clarify your own understanding or assumptions. This again reduces the size of the Hidden and Blind windows, and can also help people towards more accurate judgements.

There is more about this in our pages on Questioning Skills and Techniques.

Recognise when you are responding emotionally or making judgements that are not fully grounded in fact or observation. Try to check your facts and understanding before making a judgement.

There is more about this in our page on the Ladder of Inference.

A Final Word

Improving your own self-awareness is a good first step towards being more aware of others, and what is going on within a group. Perhaps it is fair to say that reducing your blind spots would be a good place to start for any of us wishing to improve how we work with others. These models may be helpful in thinking through some of these processes.